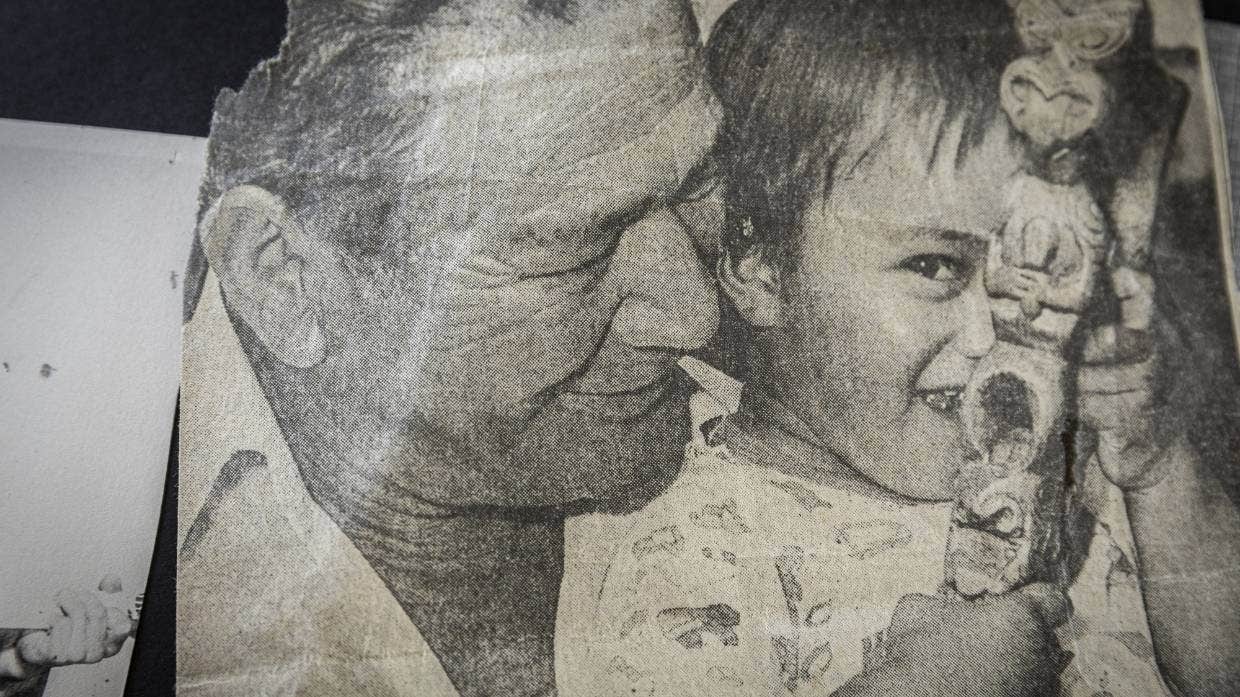

Ben McLean fought in World War II and was one of only two Māori soldiers held in the infamous Colditz prison. A fellow prisoner captured him in charcoal. Source / Supplied

By Charlie Gates, Stuff

They are the forgotten Māori soldiers of Colditz. The two men served time in the infamous German prison and went on a dangerous mission at the close of World War II in Europe. Charlie Gates uncovers their full story for the first time.

Soon after the buses pulled away from Colditz castle, the clock tower in the town below struck midnight.

It was Friday, April 13, 1945, just weeks away from the end of World War II in Europe, and a group of prisoners were being corralled onto a bus by unsmiling German soldiers with machine guns. Everything looked greenish yellow under the arc lights outside the infamous German prison. Among the prisoners were British royal family members, aristocrats, a relative of Winston Churchill, and two Māori soldiers from Northland, Ben McLean and Reginald Mitai.

For McLean and Mitai, this was just the latest terror of a long war. The only two Māori prisoners in Colditz had already been shot and captured in Crete, spent years in a brutal prisoner of war (POW) camp in Poland, and endured mock executions.

Now they feared they were being taken to Adolf Hitler’s final redoubt in the German Alps to be used as hostages in a bloody last stand against the Allied forces. They were leaving a high security German prison, but now they were entering deadly territory with deadly company.

In order to survive, one of them would confront Russia’s feared Red Army and the other would face a Nazi leader with direct orders from Hitler to kill them all.

********

Ben McLean grew up on a family farm in Rawene on the Hokianga Harbour in Northland. Photo / Michael Field

McLean was born Penamene Makarini Titore and grew up on a farm in Rawene, on the Hokianga harbour in Northland. He adopted the name Ben McLean when he became a Catholic.

He was fearless, never backing away from a fight and once facing down an angry bull.

This reputation earned him a nickname that followed him his whole life and duly ended up on his gravestone - Mad Mac.

He enlisted in the New Zealand military in December 1939, just three months after the outbreak of World War II. He was approached by a recruiting officer in his local pub and was keen to leave Northland and see the world.

Mitai, a labourer working in Pukekawa, south of Auckland, enlisted in May 1940, aged 24.

New Zealand troops resting in a village street during a lull in the battle for Crete. Source / Supplied

After training, both men shipped out to Egypt as part of the 28th Māori Battalion. In May 1941, they were caught up in the battle for Crete.

It was 20 months into the war and Germany was sweeping through Europe with terrifying speed, conquering Denmark, Norway, France and Yugoslavia. Just a month before, the German army had pushed Allied forces out of Greece. The Allies retreated to the island of Crete, but the Germans attacked again. This time they came from above, with thousands of troops landing on the Mediterranean island in parachutes and gliders.

The Māori Battalion led a fierce counter-attack against the German invasion. Their rearguard action allowed many Allied soldiers to escape once the battle was lost.

McLean and Mitai were somewhere in this hopeless fray. McLean was running from German troops when he made the mistake of looking down. His boot was filling with blood from a bullet wound. That’s when the pain started. In an interview in the 1970s, he said that if he hadn’t looked down, he may have got away. Instead, he sat down and waited to be captured by the invading German troops.

Mitai was also captured after being shot in the neck and both legs.

The battle for Crete was a disaster for New Zealand troops. These soldiers are disembarking in Egypt after being evacuated from Crete by the British Navy. Source / National Film Unit

McLean and Mitai would spend the next four years in captivity. They were given consecutive POW numbers - Mitai was 16455, McLean was 16456 - and sent to a camp in occupied Poland called Stalag 21.

Life was tough in the camp. Prisoners worked hard, doing everything from forestry and snow-clearing to drainage and farming.

Dinner most nights was a small piece of bread and soup. Otherwise, they were fed horse meat and potato peelings.

In the British National Archives, there are many reports detailing the ill-treatment and sometimes murder of British POWs in the camp. Life would have been particularly tough for Mitai and McLean.

McLean photographed before he left New Zealand to fight in World War Two. Source / Supplied

New Zealand war hero Charles Upham, who spent three years in POW camps and also ended up in Colditz, said in a 1970s interview that German prison camp guards were particularly brutal to Māori soldiers.

“The Germans were very spiteful. They hated the Māoris.”

For McLean’s first three months in captivity, he was not given any clothes.

His eldest son, Patrick Leef, said his father was brutalised by the Germans.

“He learnt how good the Germans were at torturing people. They showed him.”

Leef said his father’s stubborn streak got him into trouble at Stalag 21. More than once, they put a gun to his head in a mock execution.

“They held a gun to his head frequently because he wasn’t obedient.

“He was quite a stubborn person. It was in his nature. He was being himself.

“He threw a horseshoe at one of the guards. That was probably one of the times when they put a gun to his head.”

Mitai and McLean spent three years in the Polish camp. Then, in November 1944, just seven months before the war in Europe came to an end, they were taken to a very different prison - Colditz castle.

Colditz was an ancient stone castle on a rocky outcrop high above the small German town that shared its name. The forbidding fortress was built by German king Henry IV in the Middle Ages. It had previously served as a psychiatric hospital, a sanatorium and a workhouse and was now a high security prison for troublemakers and serial escapees from other POW camps. It was already well known for daring and ingenious escapes by Allied soldiers, who tunnelled, tricked or bluffed their way out.

McLean had heard of the place. On arrival, he couldn't help but feel daunted as he looked up at the towering battlements. By goodness, he thought. A person can't escape from here.

They had arrived at a strange time. The German army was in retreat. It had been pushed out of Russia and much of Eastern Europe by the Red Army, and Allied troops had swept through most of Italy, and liberated France. McLean, Mitai, and their fellow POWs speculated that their transfer to Colditz may have been some sort of reprisal.

Germany’s slow downfall made life harder in Colditz. Red Cross food parcels ended the month before McLean and Mitai arrived. There was not enough coal to keep the boilers running, so the castle was often freezing. The prisoners subsisted on mouldy potatoes and thin soup, which sapped their energy and brought the daring escapes to a halt. Even if they had managed to get out, the surrounding area was being patrolled by members of the SS - the Nazi Party’s notoriously violent paramilitary unit - who had orders to shoot escapees on sight.

McLean with Mabel Leef before he went to war. Afer World War Two, McLean married Mabel’s sister, Kathleen. Christel Yardley / Stuff

Despite this fevered atmosphere, McLean settled well into Colditz life. He shared a room in the castle with Mitai.

Canadian soldier and Colditz prisoner John Wood described McLean as “one of the boys” and “six foot of magnificent Māori bone and muscle”. A fellow prisoner drew a charcoal portrait of McLean that depicts him as chiselled, handsome and brooding.

McLean’s son, Patrick Leef, said his father learnt to speak German and French during his time in prison. He was intrigued by the German soldiers. Leef said the feeling was probably mutual.

“They must have found him fascinating - a little brown person ending up in Colditz.”

On the morning of April 12, 1945, the prisoners at Colditz heard distant gunfire. They knew it was the advancing American army. The prisoners had long been anxious about what would happen to them as Germany collapsed. Would they be at the mercy of the feared SS? That evening they got their answer - SS troops arrived at the castle gates.

The troops were interested in one particular faction of the Colditz POWs known as the prominente. The prominente was made up of relatives of high-ranking or prominent Allied figures. There was journalist Giles Romilly, who was related to Winston Churchill, minor members of the British Royal family, George Haig, the son of World War I Field Marshal Douglas Haig, and British soldier Michael Alexander, who had falsely claimed to be a nephew of Field Marshal Harold Alexander to escape execution.

McLean’s daughter, Noeline Gear, has photographs of her father in a family album. Christel Yardley / Stuff

The prisoners had long suspected the prominente would one day be held as hostages to be used as pawns in the war’s endgame. They feared they would be taken for a bloody last stand at the Eagle’s Nest, Hitler’s fort high in the German Alps. Now it seemed their fear was coming true.

Senior British officer William Tod argued with Colditz commanders that it would be “madness” to send out two busloads of prisoners through the ever-narrowing corridor between the advancing American and Russian forces.

But the SS got their way. The prominente were on the move. Before they got under way, the British members of the prominente demanded to be accompanied by two orderlies - soldiers who acted as personal servants to the senior officers.

The word went out to the prisoners for volunteers and two men stepped forward - Reginald Mitai and Ben McLean.

The group of about 30 were then ushered through the gates of Colditz, where they were greeted by a double line of SS soldiers with machine guns and an Alsatian dog, lurking at their feet.

McLean, interviewed in the early 1990s, said he knew these soldiers were different from the German prison guards.

“There was no leader, just SS soldiers - they didn’t listen to [other] officers. No way. They were the big guns, their officers were the ones giving orders. That’s quite different. Those are the truly evil soldiers.

“At this point, everything turned sideways.”

The armed soldiers formed a corridor leading them to two ramshackle buses, an armoured car and two motorcycles.

The hostage group was ordered onto the buses. They left just before midnight and headed east. In the early morning, they passed through the ghostly ruins of Dresden, newly destroyed in an Allied firebombing. As the sun rose, there was no dawn chorus, just a stony silence.

They eventually reached another ancient castle, this time the fortress of Königstein near the German border with what is now the Czech Republic.

Here, Mitai and George Haig were left to look after aristocrat Charles Hope, who was too ill to continue the journey. McLean and the rest of the prominente headed south and eventually arrived in a military camp in Austria.

It was here that they fell under the power of Gottlob Berger, as senior leader, or Obergruppenführer, of the SS. Berger, a ruthless and committed Nazi who supported the Holocaust, arrived in an enormous black Mercedes-Benz. McLean later described him as “formidable”.

He had just returned from a meeting with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, he told McLean and the assembled prominente. Hitler had personally given him a direct order.

He was told to kill them all.

*********

Back in Königstein, the castle was proving a peaceful respite from Colditz. And, unlike Colditz, this place had plenty of food, which Mitai cooked for his two charges.

The castle afforded magnificent views across the River Elbe and Eastern Germany. But soon, that vista was spoiled. The feared Red Army - looting its way west into Germany - was advancing. Haig could see them from the castle balcony.

“They advanced in small groups across the landscape - tiny dots darting from scene of havoc to scene of havoc, burning and looting as they went,” he later wrote in his memoir.

Soon, the soldiers were crossing the River Elbe and making their way up to Königstein. Chaos followed. Drunken Russian soldiers filled the castle, searching for food, drink and treasure to steal. A German officer, who had hidden in the castle grounds, shot himself dead.

Mitai was caught up in the fever of liberation. After years in German prisons, he was finally free. He drank a bottle of brandy and began to weep.

“Years of privation had brought his pent-up emotions to the boil,” Haig wrote.

Earlier, Mitai had been entrusted with a key to the food store, which they now needed to open, so they could feed the many captured German soldiers at the castle. Haig asked Mitai for the key.

“He refused, since the key was for him a symbol of his power over the enemy who had caused him so much suffering.”

There was a struggle and Mitai seized Haig around the throat.

“He was stronger than I and, in spite of my struggles, I felt myself weaken in his furious grasp.

“I thought he would kill me. Luckily, some streak of sense in his nature took control and he relaxed his hold and gave up the key.”

Mitai fled the castle with the Russian soldiers and Haig never saw him again. Two weeks later, American soldiers arrived to take Haig and Hope to safety. They had to leave in a hurry, but Haig made the soldiers promise to return to collect Mitai.

*****************

Ben McLean’s children keep his memory alive in family photo albums. Christel Yardley / Stuff

Back in Austria, SS leader Gottlob Berger was telling McLean and the assembled prominente about his meeting with Hitler and his orders to shoot them all.

After a dramatic pause, he revealed he had no intentions of carrying out that order. Instead, he would take them safely in a convoy to hand them over to the Allied forces. (Many believed this was a cynical ploy by Berger to avoid a harsh sentence in the inevitable war crimes trial that would follow Germany’s defeat. If that was the aim, it worked. He spent six and a half years in prison for his war crimes, while many other Nazi leaders were executed.)

They set off in trucks through the Austrian valleys. It was a tense trip. They worried the German convoy would be attacked from the air by Allied planes. They also feared being taken hostage by a rogue SS leader, who was apparently patrolling the nearby mountains with a roving band of soldiers, keen to fulfil Hitler’s death sentence on the group.

But, before Berger handed the group over to the Allies, he had a surprise for them. As night fell, the convoy pulled into an isolated Austrian farm. They were ushered into a long, dimly lit hall with a table full of food and drink. It was more food than the prisoners had seen in years. Prominente member Michael Alexander wrote in his 1954 Colditz memoir that Berger entered the hall in a white jacket. “His face was shining, his eyes were bright.”

He presented them with a red leather case. Inside, sitting on red velvet, was a large pistol inlaid with ivory and enamel. Golden oak leaves ran up the barrel and on the butt was a small plate engraved with Berger’s signature and the emblem of the SS. He said the pistol, which had been given to him personally by Hitler, was an offering to prove he would deliver them safely to Allied hands.

In a later interview, McLean recalled that this was the moment he realised the war was finally over and he had survived. He wept.

”All the soldiers below me, all the same… tears flowing.”

Ben McLean’s daughter, Noeline Gear, said her father would get emotional if he was asked about the war. Christel Yardley / Stuff

******

McLean was eventually driven to the Austrian town of Innsbruck and the safety of the US Army. He arrived back in New Zealand on February 27, 1946. He had been away for nearly six years.

It is not clear how Mitai got out of Königstein, but he was back in the UK by May 15, 1945 and back in New Zealand by September that year.

After the war, Colditz became part of British popular mythology as memoirs, television shows and even a board game mined the prison for stories of derring-do, high spirits in the face of adversity, and outlandish escapes. But McLean and Mitai’s story was never fully told.

They were mentioned in despatches - the lowest honour awarded by the military - but with no details about why it was granted.

Charles Upham made a point of mentioning them in interviews about Colditz. A 1946 interview with Upham named them as V McLean and R Mitai. In a 1970s interview, Upham forgot Mitai’s name.

In the many books and memoirs written about Colditz, McLean and Mitai are sometimes mentioned. They are referred to as “Māori orderlies”. McLean is never named and Mitai is only referred to by his second name, which is misspelt as Mittai.

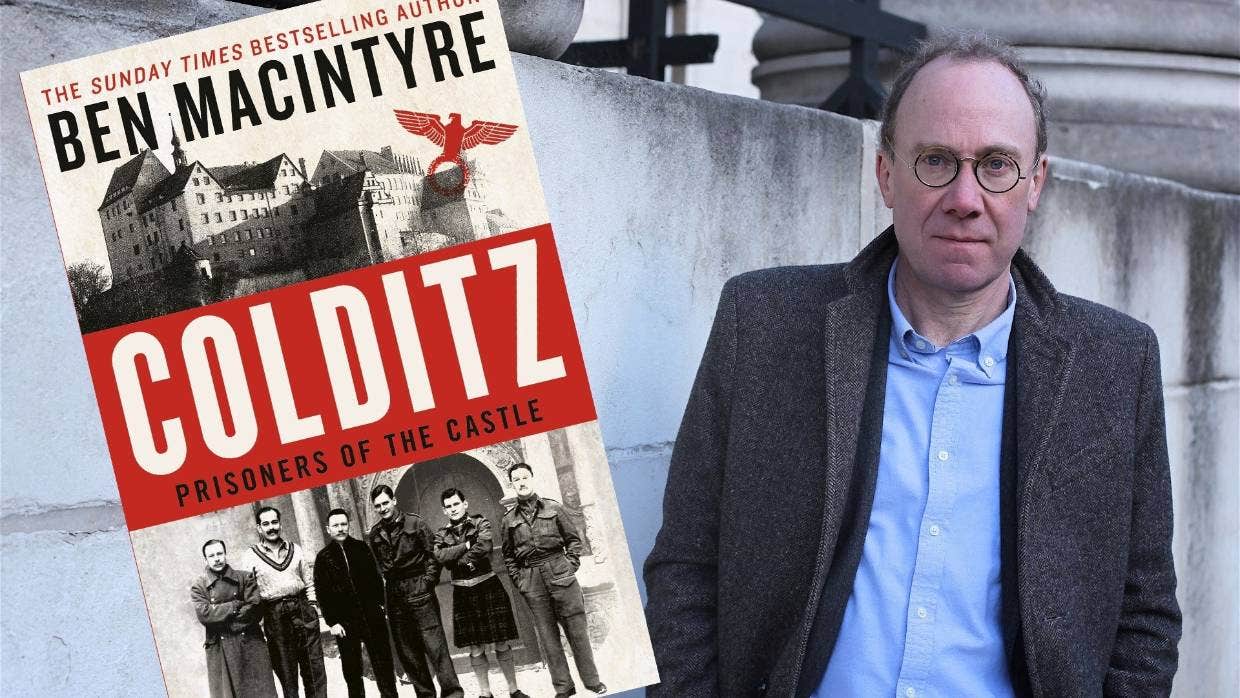

Ben Macintyre's new book about Colditz mentions Mitai and McLean, but does not name them. Source / Supplied

British writer Ben Macintyre struggled to find any record of them both when researching his new non-fiction book Colditz: Prisoners of the Castle.

“I have not been able to find out anything about them,’’ he said in Christchurch during a New Zealand book tour.

“This is just another example of the way the class system worked. It wasn’t deemed necessary to record their names.”

This story was pieced together from interviews with McLean’s family members, contemporary memoirs, a Colditz Society article by David Ray, a brief newspaper interview McLean gave in the 1970s, and a te reo television interview with McLean on Waka Huia in 1993.

Reginald Mitai moved back to Auckland after the war, where he worked in various jobs, including a spell at the Chelsea sugar factory. In the late 1940s, he changed his name to Cedric Brass. He died in 1970 at the age of 54. Relatives of Mitai could not be found, despite extensive efforts.

McLean in the early 1990s, working on oysters from his Hokianga Harbour farm. Source / Supplied

McLean returned to the Hokianga where he ran a small beef and pig farm. He later farmed oysters in the harbour. The frames he built to grow them on are still there.

He married Kathleen Leef. They had 11 children, but he didn’t share war stories with them. His son, Ben McLean, said he kept quiet about his service entirely.

“He did a really good job of keeping it all in and carrying on.

“He cut loose in the RSA. To be a fly on the wall there would have been a good thing.

“He used to come home from there really happy and talking German.”

Noeline Gear said her father was “awesome”. Christel Yardley / Stuff

Noeline Gear said her father would get emotional if asked about the war.

“It brought back memories for him.

“When one of the kids sat down and asked him questions about the war, he would cry. He would say: ‘That’s enough’.”

His oldest son, Patrick Leef, said the trauma of war was handed down to the children.

“The violence affects people psychologically and that was passed down through the family to us.

“It has had a massive effect on the brothers. It has screwed them up. They are not really moving forward in life.

“He wasn’t overly violent. There was a different type of violence going on inside him. As boys, you pick that up and carry it into your own lives.”

Leef said his father handed down one useful lesson from the war.

“He taught me to respect the violence that Pākehā are capable of inflicting.

“It was a valuable lesson. It helped me get through life.”

Ben McLean fought in World War Two and was one of only two Maori soldiers who were imprisoned in the infamous Colditz prison. Source / Stuff

McLean died in 1999 at the age of 79.

Leef said the Māori sacrifice in World War II did not lead to a better life after the conflict.

“It didn’t really make any difference for the Māori people and how they are being treated today.

“They got dumped after the war and society forgot about them. What was the point of it all?”

On McLean’s first day back in New Zealand after returning from war, he went to the local pub. The barman refused to serve him because he was Māori.

The local policeman intervened and insisted that McLean should be served. Then they sat down and shared a pint together.

Te reo interview transcription by Joel Maxwell and translation by Taurapa.