The year was 2010. We had walked for seven and a half days to get to a village called Dolphu, on the border of Nepal and China in the upper Himalayas- a journey the locals had said would take us two days. Armed with a tiny camcorder, we were trying to get a shot of the elusive snow leopard. We got none of that. To add to the disappointment, we also heard dire stories of doomsday turning into reality.

In every house that we went to, elders seated around fireplaces or on verandahs of mud houses pointed at the towering hills and mountains around us and talked about how high the snow line had receded in their lifetimes.

It's a part of the world where poverty hits hard. It’s a part of the world where after millennia of subsistence farming and barter, globalised commerce has taken hold and people have started working for cash to spend on buying things hitherto not needed. A place where finding employment outside of cultivating one's own fields has suddenly become a necessity.

One of the ways children in the region make that extra cash is by harvesting Yarsagumba (Ophiocordyceps sinensis)- an odd half-bug half-fungus that is much sought after in the Chinese market where it is sold as a supposed aphrodisiac. Every year, hundreds of kids (whose eyes are sharper and better adapted to spotting the dead bug buried in the soil with a fraction sprouting out) skip school and march up the hills, risking high-altitude sickness, camping and scouring the grounds for yarsagumba.

These kids- teenagers who were at the time prepping for the next picking season a few weeks away, pointed at the hills and showed us where the snow line was this time of the year in the previous years and how it had moved in their lifetime. One even profferred what he had heard in conversations - that the snow line would go farther up until there was no snow left. They could then go higher up to collect more yarsagumba, and make more money, he reckoned.

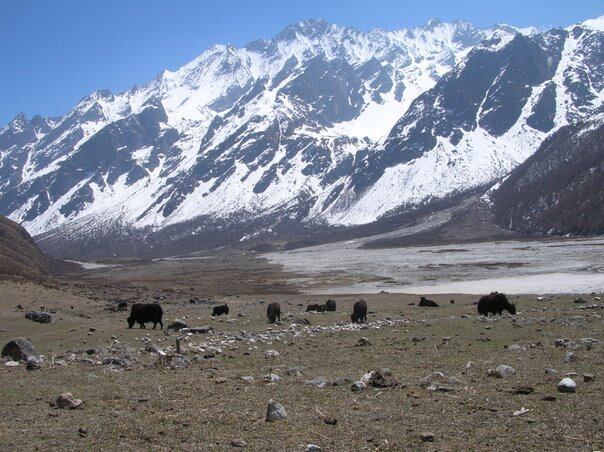

A village in northwestern Nepal. The old and young alike share accounts of receding snow line, thinner snow cover and shorter snow seasons. Photo: Supplied/ Samrat Katwal

Halfway across the world, on a Tuesday morning, in what I can only imagine was a tightly packed corridor on the third floor of the parliament house, a sitting New Zealand MP said she was yet to see the evidence of human impact on climate change. She walked back soon enough but the day’s proceedings went on to show that climate change denial is as real as climate change, and perhaps just as big a problem.

And yet, as someone from the developing world, I still can’t help but be surprised every time I hear this denial coming from quarters that I should now be used to - the most affluent of people who benefit from everything that speeds up climate change. Republican presidential candidates in the US, billionaires, European far-right parties, oil and coal companies, Donald Trump and Trump-like world leaders, as well as conservative media outlets have proffered varying levels of scepticism.

That the climate is changing and human activity has hastened its change is not up for debate. All the more so among policymakers and people in power, as this piece in the Newsroom last week put across.

For indigenous people around the world, that privilege of scepticism is as far removed as the air-conditioned office of a member of parliament in a developed nation. Nomadic herders and farmers in the Himalayas are walking in the shadows of melting glaciers. Kiribati could see its land engulfed by sea, as could the Maldives. Tribes in the Amazon are witnessing a rainforest transition into a savannah. Widespread famine and crop failure in Madagascar has seen people scraping by on raw cactus and locusts.

A 2021 World Bank report projects 216 million climate refugees by 2050. Going by UNDP and UNHCR's figures, that's just over twice the number of all refugees that are in the world right now- this world with all its wars and persecution.

Communities on the frontline of climate change have little in common with climate change-denying politicians in developed countries. Photo: supplied/ Samrat Katwal

The bulk of those displaced by climate change will come from the poorest parts of the globe- sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America. Small in number but hit just as hard will also be the entire populations of sinking island states.

So while it might be all right for a sitting MP in Aotearoa, a fairly affluent person in a fairly affluent nation to say she's yet to see the evidence for human impact on climate change (and life will not change drastically for her, nor will her party ranking), spare a thought for those that are at the frontlines of climate change, for people who have shared a habitat with other species for millennia and are now seeing it shrink, for people who have contributed the least to whatever is causing this shrinkage, and for the kid in Dolphu who is looking forward to climbing higher on increasingly barren mountain slopes in his search for yarsagumba.

Rituraj Sapkota is a Te Ao Māori news video journalist and a documentary filmmaker from Nepal.