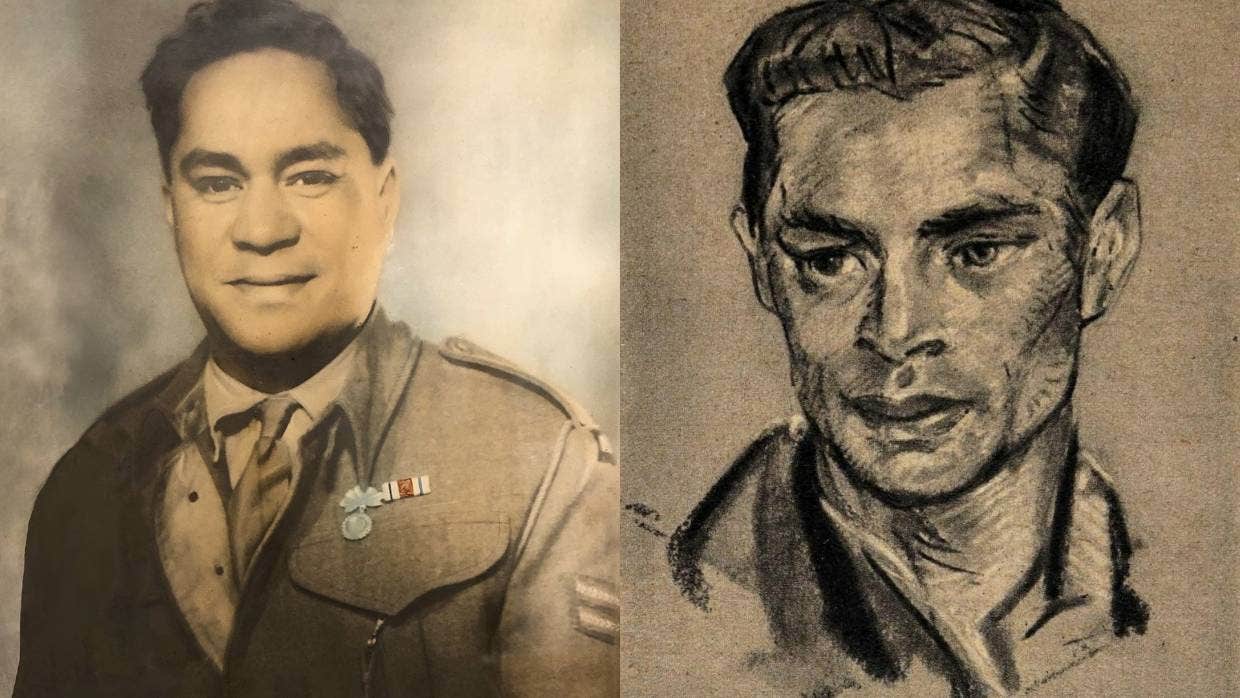

Cedric Brass was one of two Māori soldiers who served time in Colditz during World War II. Source / Supplied

By Charlie Gates, Stuff

The first time Elaine Marsh discovered her father had served time in Colditz Castle during World War II was a phone call four years ago.

Her father, Cedric Brass, never told them anything about his wartime experiences, let alone his spell in the infamous German prisoner of war camp.

A recent Stuff feature told the story of the forgotten Māori soldiers of Colditz. The two men, Cedric Brass and Ben McLean, were imprisoned in Colditz – an ancient stone castle on a rocky outcrop high above the small German town that shared its name.

The pair went on a dangerous mission together at the close of World War II in Europe. They were taken hostage by Nazi soldiers, along with members of the British royal family, aristocrats, and a relative of Winston Churchill. Brass was eventually liberated by Russia's feared Red Army as it looted its way through Germany.

But Brass’ life remained a mystery. There was little trace of him in archives and living relatives could not be found, despite extensive efforts.

After the story was published, family history researchers came forward with information that led to Brass’ two living daughters: Marsh and Kathleen Parata. They were able to cast light on why his life was such a mystery.

Brass changed his name to Reginald Mitai when he enlisted in the army to disguise the fact he was underage. Once he returned to New Zealand, he reverted to his birth name – Cedric Mitai Brass – and rarely spoke about the war. He was known by friends as Bobby Brass or Robert Brass. He died in 1970.

His daughters knew him as a gifted car mechanic, a gentle father and a troubled man.

Brass, left, and Ben McLean went on a dangerous mission together at the close of World War II. Source / Supplied

Marsh only learnt about her father’s Colditz connection when she was contacted by Māori Battalion researcher Harawira Pearless in 2019. Such was her father’s anonymity, it had taken Pearless three months to find her.

“I wish he had talked to us a bit more about it,” she said.

“My dad became a bit of a recluse about his war time. A lot of the POWs were ostracised by the other soldiers.

“I would love to have known more.”

Brass, right, before he headed to Europe to fight in World War II. He spent several years in POW camps. Source / Supplied

Marsh said her father was traumatised by the war, mentally and physically. Learning about his time in Colditz helped her to understand why.

“There was a lot going on in his mind.

“I think his drinking may have been from the trauma. I think he was traumatised by a lot of things. He got angry sometimes.”

Parata said her father had a phobia of jangling keys, which she believes came from his time in Colditz.

“He wasn’t himself when he got older. He was very agitated and had a lot of anxiety.

“When you think about it, I believe his anxiety was from the war.”

Brass was remembered by his two daughters as a loving father and a gifted mechanic. Source / Supplied

When Brass returned from war, his siblings ostracised him, Parata said. Their mother had died while he was away.

“He ran away to war and changed his name. His siblings accused him of killing his mother.

“They said she died because she lost him. They said she died of a broken heart.”

Parata and Marsh both remember Brass as a gentle father.

“He was a mellow sort of a man. He was a good dad,” Parata said.

“He was a very soft man. Mum was the one that gave us a telling off.”

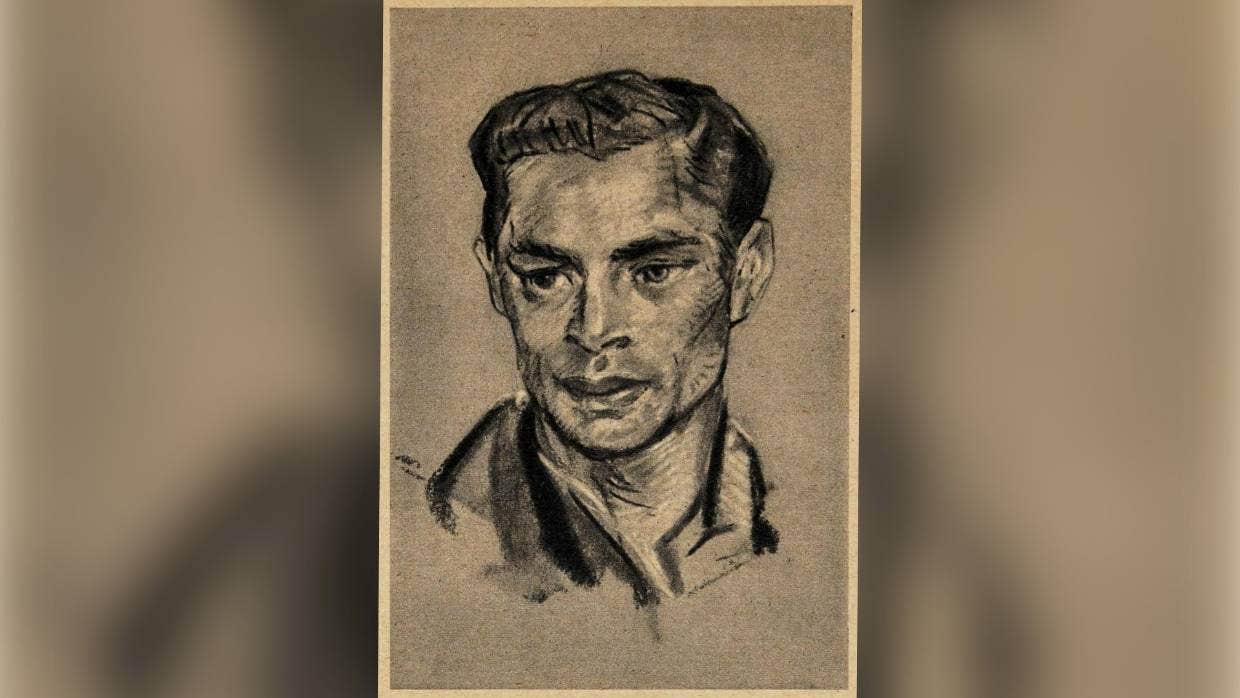

McLean fought in World War II and was one of only two Māori soldiers in the infamous Colditz prison. Source / Supplied

Brass worked as a mechanic for the council in the Auckland suburb of Point Chevalier.

“He was good with anything that had wheels.

“He knew what was wrong with a vehicle as soon as he turned it on.”

Elaine Marsh said the Stuff feature taught her more about her father’s wartime experience.

“It amazes me what they went through.

“It makes me a bit teary.”