Te Ao Māori News videographer Rituraj Sapkota explains what it's like working among reporters and politicians in Parliament.

The Parliament Press Gallery is an interesting but strange place. People who work in the different rooms here are not colleagues; to the contrary, they are competition.

With most press conferences coming out of the Beehive being broadcast live on many linear and digital platforms, reporters have become household names, and the public hears all the questions that politicians get asked.

Often you hear reporters talking on top of each other, and at times you, the audience, complain in the comments section about the questions they ask.

From behind the camera at the end of the room, my view is different. I see hands being raised, for minutes at an end sometimes, awaiting their turn to ask questions, and I witness solidarity.

Although the media in this country are competitive, there are no dog-eat-dog 24-hour news channels trying to break news stories. That’s why, if a politician leaves a question unanswered and moves on to another journalist, it is not uncommon to hear a “can you please answer the previous question first?”

In their faces

Working behind the camera in Parliament is fascinating. The breadth and depth of kaupapa dealt with are mind-boggling.

The petitions that come to Parliament range from asking Pfizer to fund a certain cancer drug, to demanding action on climate change.

The select committee hearings offer a variety of perspectives and important arguments on both sides of the debate.

Every Treaty settlement opens up a new chapter in history I had never heard about before.

In addition to that, the job gets me up close to the people who run the country. We are right in their faces, and I get to observe all the non-verbal cues our cameras don’t pick up. I see what they do with their hands and how they stand on their feet, the pauses they take and the glances they throw at the speaker beside them.

My journey as a press gallery videographer started in June 2019, despite me only a few months earlier swearing off news. I took on a job that thrust me to the centre of it.

It takes a while to get used to the pace of the Press gallery and the media “scrums”.

It can be a fairly intimidating situation for any newcomer - even reporters take a while to find their voice in those scrums and press conferences.

For a new camera-op, the struggle lies in not disrupting the next person’s shot, while standing shoulder to shoulder; not stepping on someone’s toes while forcing your way into a scrum (I have stepped on my fair share of toes), and finding the confidence to tap a reporter that you have seen on TV on the shoulder and ask them to move out of your shot. Eventually, you get into the groove.

For me, all this is made all the more fascinating by the fact that I am an outsider - a non-New Zealander and a second-language English speaker (there aren’t many of us in the Press Gallery.) And, as another year in the job draws to an end, here’s a throwback to some memorable moments from the perspective of someone who brings to your screens the sights and sounds of the halls of power in this country.

Sorry, can you repeat that?

This one is not from 2021. This is the first incident in this job that is etched deep in my memory. It was a sitting day of the Parliament, and our Press Gallery reporters weren’t in that day.

The newsroom in Auckland needed to get some answers from some MPs at the ‘Bridge Run.’ I was asked if I could ask them the questions. New to the job, and eager to impress, I agreed.

The ‘Bridge’ is the part of the building that connects the Beehive to the Parliament building. The prime minister, cabinet ministers, and the other MPs, mostly from the government, walk across it, enter the Parliament building foyer where they stop and take questions from the media. A horseshoe-shaped “scrum” forms around the politician: TV cameras go in the centre, the TV reporters stand beside them and the radio and print journalists stand on both sides of the MP. There is a designated ‘scrum’ for the prime minister and other ad-hoc horseshoes form around any MP a reporter may stop to ask questions to.

I needed three MPs. The first I quickly pulled to the side as he walked into the foyer, asked him the question, recorded his answer. Done. The second I caught just before she crossed the “no media beyond this point” line near the entrance of the debating chamber. Question, record, thank you. Dusted.

The third, an associate minister was in the middle of a scrum. I scuffled my way into the horse show. All around me questions were flying; voices (the top ones in New Zealand’s broadcast industry) were competing to get their questions in. There was a micro-second of pause after one answer. This was my moment.

I spoke. Now mind you, my job as a cameraman is to be invisible and inaudible behind the camera. Also, English is not my language. I often have to repeat myself because people can’t understand me in normal conversations.

This was me when I was nervous. I rushed through my question, and it was a long question! Around me, I could feel all eyes on me. The minister smiled and nodded throughout what felt like an eternity, and after I finished, she leaned closer (this was pre-Covid times) and said: “Sorry, can you repeat that?”

I roto I te reo Māori?

Fast forward to 2021. By now, I was more comfortable in scrums and the rush of the job. One of the goals I set myself for 2021 was to ask a Māori-speaking politician a question in te reo Māori. The perfect opportunity arose early this year when my reporter colleague, away on another shoot, messaged me to ask if I could ask a particular minister a question at Caucus Run.

A quick explanatory note on what caucus runs are. The MPs of the two largest parties (Labour and National) have their respective caucus meetings on Tuesday mornings (the start of the parliamentary week) before they head to the debating chamber. Labour’s starts at 10am so the media line up in the corridor outside their meeting room on the first floor to ask questions before they enter. We then run up to the third floor to continue the same exercise with the National MPs.

I am in the main scrum, camera in one hand, mic in the other, ready to pull out and stop the said minister when he arrives. I have translated the question in my head, memorised and rehearsed it, intonation and all. From the corner of my eye, I see the minister squeeze past the horseshoe and walk away, and quite briskly at that. I chase after him (it’s called Caucus Run for a reason) and catch him just by the door at the end of the corridor.

“Tēnā koe e te minita, he pātai mau.”

He turns, straightens his tie and looks into the camera.

He sees the Māori Television sock on the mic. “I roto I te reo Māori?” he asks.

“Āe,” I respond. Suddenly three journalists appear around me and a scrum has formed. I am in the centre of it. They are all holding their mics up, and looking at me.

My brain has never been my ally. My reo goes flying out of my mind, across the long corridor and out the window.

Two years of poring over dozens of books, translating scripts, and countless imaginary conversations: it all disappears in two seconds. I hesitate, and you can’t hesitate in a scrum.

“Yes, please,” I repeat and proceed to ask my question in English.

Axe to Parliament

New Zealand’s parliament is very open to the public. While access inside is limited, there are still guided tours happening on most days, and the outdoor area is pretty much a park.

On a good day, there’s a crowd of people sitting on the lawns, having coffee or lunch, or just chilling out.

It’s unlike most other places in the world, where it’s not so easy to get close to a government building. [And when a crowd does, it’s not always for good reasons!]

Six days after the US Capitol riot, in a completely unrelated move I must add, a man decided to have a go at New Zealand’s seat of power. At a most commendable time of 5:30 am, he attacked the glass doors of Parliament with an axe. He was apprehended and brought before a judge in a rarely used basement room in the High Court across the street, where media teams were not allowed (another rarity - the size of the courtroom was cited as a reason for this).

Thankfully, nobody was harmed. It was a hot topic for a couple of days and then, as with all news, it died out.

My starting point

More than individual memories, Waitangi for me was about the overall experience. I was up there for a week, filming, observing, and learning.

I had been in the country for five years but my knowledge of the founding document of this nation was abysmal, as I am sure is the case for many people, including those born here.

But being a part of the Waitangi Day celebration for the first time, walking (and almost tripping) with my camera and tripod along trenches in Ruapekapeka dug 155 years ago, hearing descendants from both sides of the battle make commemoration speeches, and filming for a dozen kaupapa over the week opened up chapters in history, ones that immigrants like myself are not even remotely aware of.

Waitangi, much as it is the site for the foundations of this nation, is also the starting point of my journey in reporting. It was here that I compiled what was my first report for television in New Zealand, and my first report in te reo Māori. The first of many to come, hopefully.

I can go but I can’t come back

In July, the prime minister was to have travelled to Australia. As with most foreign trips, she would be accompanied by a media entourage.

The newsroom planned for me to go with my reporter colleague to film and cut stories to send back.

When the team told me this, my instinctive response was “I can go, but I can’t come back.”

That was met with visible confusion, and I explained that as a non-new Zealander, and a migrant worker on a temporary visa, the borders are still closed to me. So, if I were to travel to another country, I would not be allowed back in, and that would have made for quite ironic scenes at the airport.

The trip was postponed in the end after new Covid-19 cases swelled in New South Wales.

‘Fake media, go home’

The part of my job I like the most is packing my gear and going out of the Press Gallery into the regions. Te Tai Tokerau is hands down a favourite.

Both my reporter colleagues are locals there, and the weather is the opposite of what it is in Pōneke.

My trip there in August this year was cut short after the nation went into level-4 lockdown.

I went back there in early November when the vaccination drive was in full swing. Northland had one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country but people were mobilising and stats were fast on the rise.

I saw young teams drive up from Auckland, set up vaccination sites, hold banners, dance and create an almost festive atmosphere across towns in the Far North. While filming, I saw them talk to and bring to the kiosks about four to five people to get their first shots in just a couple of hours. But away from these vaccine kiosks, things were not so festive. We got honked at and given the finger by people as they drove past, and twice I got asked by people that pulled up beside me what I was filming and if I was there to push vaccines.

On our third day in Northland, we went to a vaccination site. There were a handful of protesters picketing outside. There was even a girl (she couldn’t have been more than eight) holding up a sign that said Covid-19 does not affect children. Two days later, it was announced that there had been a Covidhospitalisation in Whangārei of a six-week old baby.

As soon as we got out of the car and walked up to the site, we heard a voice yell “Fake media, Go Home”. My colleague pulled down his mask and shouted back “I am home.” Comeback of the year that!

Later when we were walking up to our car after filming, a woman came up to us (right up in our faces) and with a distinct American accent asked us if we would only tell "one side of the story."

"Isn't it communism?" she asked, "to only tell what the state says?" We ignored her and loaded the car. She also said it was a bloody nice car and that nobody in the media could afford a car like that. (It was a rental SUV), and said the government must have paid us out to push their narrative. She then proceeded to stand in front of our car, reminding us that it was taxpayers' money and so she had paid for it. I started to roll down my window, intending to thank her for it, but a police officer convinced her to move aside and let us pass.

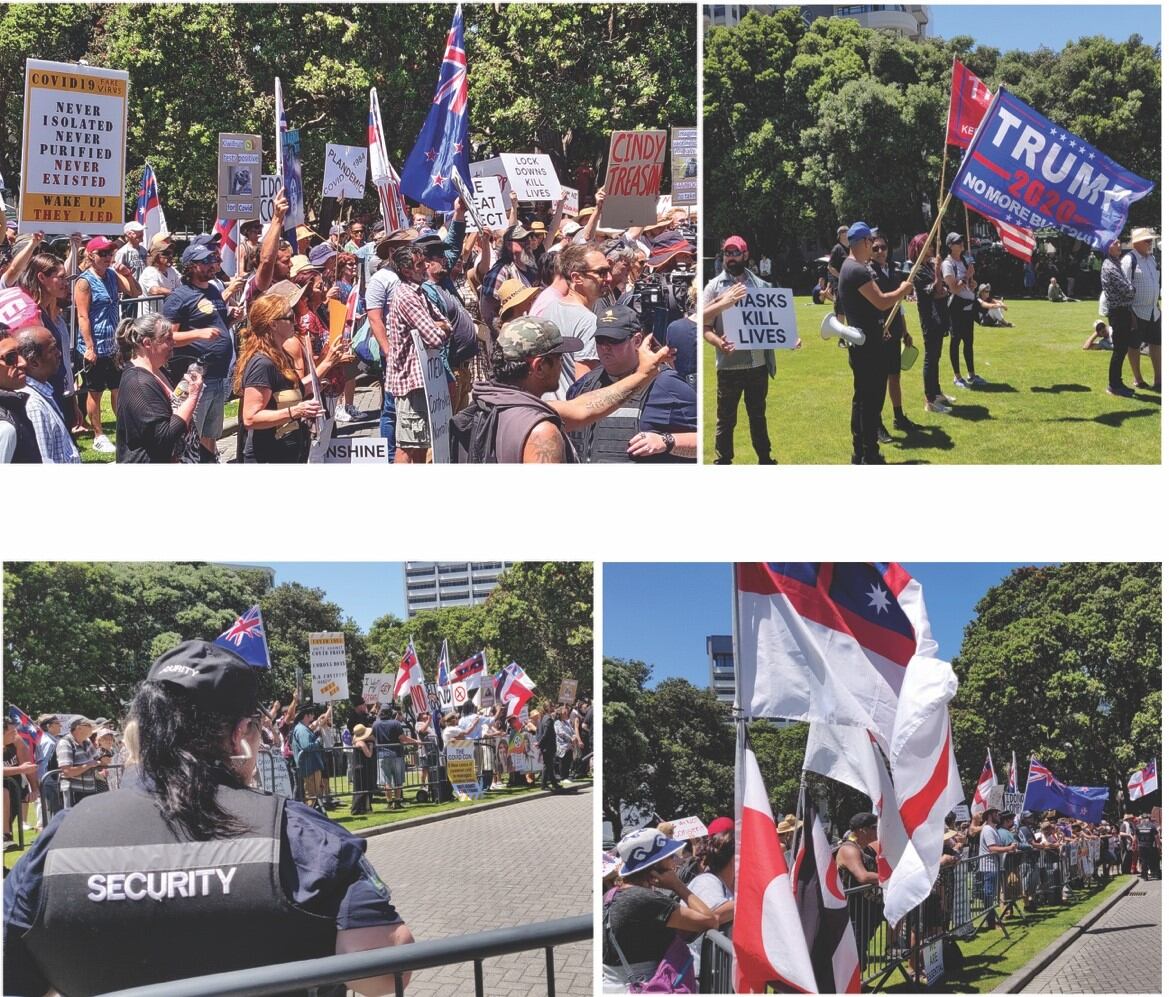

It was a little unnerving episode, but it was nothing compared to what happened with our colleagues in the Press Gallery the next day, as thousands gathered in front of the parliamentary buildings in Wellington - loud, angry and protesting a wide array of things.

Protests outside Parliament are not uncommon - in fact they are an important part of a free and functioning democracy. I have filmed quite a few in my short stint there, but this was different. This day saw police presence like never before, and the media that protestors traditionally rely on to disseminate their messages became targets of the protesters.

The National saga

Towards the end of November, the National party had a leadership change. Again. (In the couple of years I have been here, I have now seen three). The day began with the press gallery chasing MPs on their way into the caucus meeting. And by chasing I mean what you see in the photos here captured by Stuff’s Press Gallery photographer.

The caucus went into the meeting at 9am, with a press conference planned for 10 AM in the Legislative Council Chamber. This room used to be New Zealand’s Upper House until the council was abolished in 1951. It is now used for press conferences and other formal gatherings. Reporters and camera ops took their seats shortly before 10, Another group of camera ops lined up outside to get those important walking shots of whoever the leader was at the end of the meeting. Their meeting went on until after 1pm. For four hours, the media waited for the next leader to walk in. Those were also four hours without coffee or breakfast because we knew they would probably walk in the moment we left our positions.

There were a lot of sore legs. And all the TV reporters took turns at going live on their respective news bulletins with the latest updates, most of which was that we were all still eagerly waiting.

Interestingly, that day was also my first time being in front of the camera during a live cross. It’s not what you think, though. I was in the background of a five-minute-long segment on a major national channel’s midday bulletin, behind the reporter, out of focus, scrolling on my phone, and at times casually stroking my belly, perhaps because I was hungry. And if there is one segment in the article I will not share pictures of, it’s definitely this!

This year has really flown through. Here is to hoping that 2022 is the year we triumph over this pandemic, the year we can start thinking of international travel again, and hopefully even the year I find it in me to ask that pātai i roto I te reo Māori!