“I have never had that fear before that I might get physically hurt,” says Patrice Allen, a Ngāti Kahungunu and Newshub camera operator based in Wellington. “You’re going down there, you don’t know what it’s going to be like. A person from Wellington Live got beaten up.”

Māori Television’s press gallery videographer David Graham (Taranaki Whānui and Waikato) started working as a news cameraman in Wellington in 1989. He was there for the seabed and foreshore protests, and “in the 1990s it was Moutoa and Pākaitore,” he recollects. “But this is the most volatile one I have seen.”

“Back then we (the media) were part of the show. They wanted us to be there. Now we are a part of the ‘axis of evil’, along with the police and government.”

Up against your own

"Now there are Pākehā calling you kūpapa," he says. He has just returned from filming with his phone in the crowd, and has heard protestors say things. Nasty things. "Stuff like 'you should be ashamed of yourself. You should be ashamed of your whakapapa!'"

"I just don't engage," says Graham. "And I am not a random man with a camera here. I actually whakapapa back to this marae on my father's side," he says, referring to Pipitea Marae where Taranaki Whānui laid down Te Kahu o Raukura as a cultural protection over the surrounding land that includes the parliament grounds.

(The protestors had lots of livestreams and many of them kept filming media camera-ops who were filming them. Above: David Graham finds himself in one of the live feeds while a protester in the crowd heckles him.)

Allen feels the mamae is stronger when it comes from your own people. “This happened on the day of the last protests,” she says, referring to the protests in November where the crowd threw tennis balls and water bottles at the media. She was filming a timelapse of the crowd leaving when a mother-son duo walked up to her. “He was a big dude and he was really getting in my face. I was not feeling very safe. And I thought, 'how can I diffuse this?'” So she asked them where they were from.

"And they were like where are you from? What are you?"

“Oh, Ngāti Kahungunu, just over the hill in Wairarapa,” she replied. The man said something targeting not just her but also her iwi. “And that just broke my spirit,” says Allen.

“It was one of the days I went home and cried.”

'This is hard to switch off'

“We are the enemy now,” says Allen. “And there is nothing you can do or say that will change their minds.”

Her teammate, Emma Tiller, thinks the camera can be a beacon in the crowd. “As soon as you put it up, everyone knows who you are. And they hate you.”

And even though security cover has become standard practice for all news camera-ops filming in the crowd, there are times she feels vulnerable. “It’s hard to think back to protests when we were out there. We didn't have security with us. It didn't even cross our minds. But now who wants to risk the violence?” she says.

“They have thrown things at the police. If they can do that to them, what can they do to us?”

The Speaker’s balcony is empty today (above). A far cry from last Wednesday when it was packed with camera operators and reporters (below). The balcony had been allocated by the Speaker of the House to media personnel as a safe space. Left: David Graham. Third from left: Patrice Allen.)

“The last time I had security was when I was filming in East Timor,” Allen. says It was a long time ago, she adds, and at a time and place when there were terrorists around. “It’s really bad because it’s made it ‘us and them’, media against protestors, and it’s not supposed to be like that.”

Sam Anderson, 22, is TVNZ’s camera operator at the press gallery. “It has been difficult to turn off,” he says “ I have been there (on the Speaker’s balcony) from 9am to 6pm just streaming the whole day. It’s all you are doing - copping the abuse, being yelled at, having your morality questioned.”

“I sometimes hide behind the pillars from the frontliners who can yell all day.”

“And throw that in with reading all the signs around you,” says Tiller. “And they yell at you. And you go home and you can’t switch it off.”

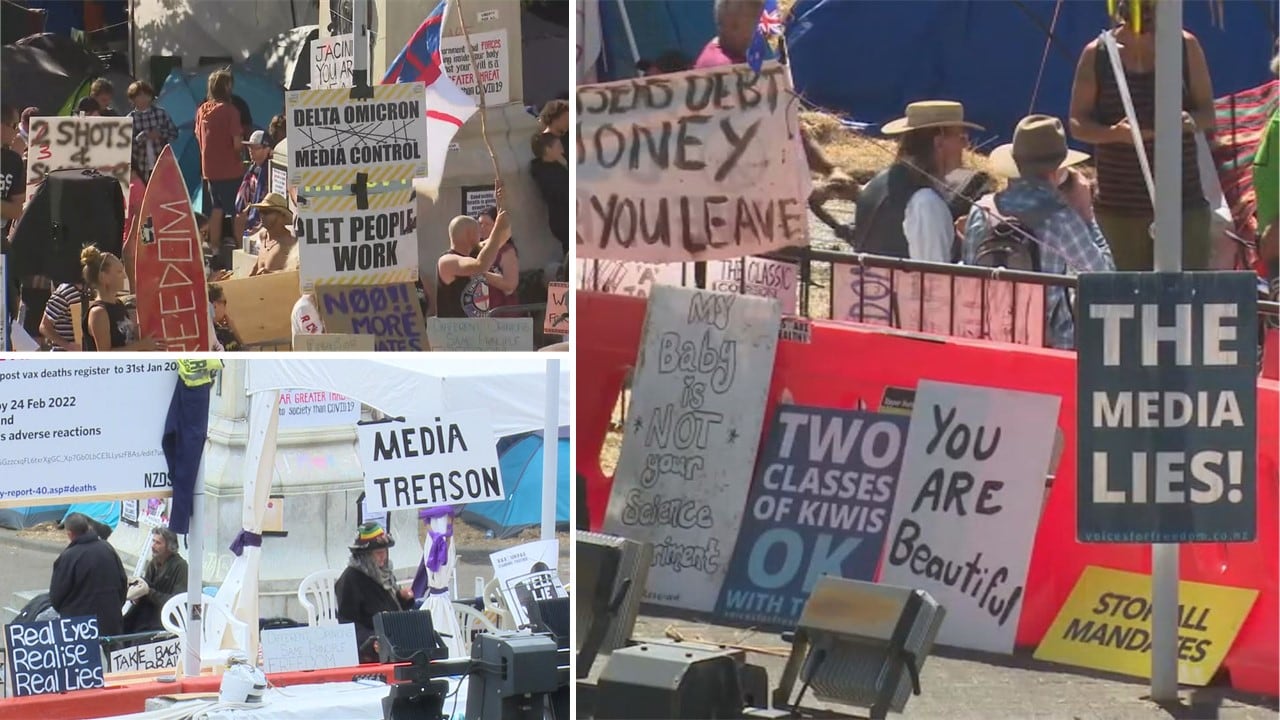

Throughout the protests, the signs have been as much anti-’mainstream’ media as they have been anti-government

Anderson’s teammate, Sam von Keisenberg, was on that balcony on February 11, when police made many arrests. Shortly after they arrested someone at the forecourt and the crowd was yelling at the police, a lady pointed a finger at him and said “You! You are a paedophile protector!”

“At first I was like, 'that’s new'. But then she said it 50 times, as loud as she could, just at me.”

He pulled his camera off the tripod. “It was getting to me”, he says. “I have children. I would never protect a paedophile.”

His colleague asked him where he was going. “Just to punch some lady in the face,” he said, under his breath. “And I walked out and just went to the bathroom.”

Sweeping generalisations

“Sometimes you have to take a step back,” von Keisenberg says.

“I had never experienced hate [directed] at me before,” RNZ video journalist Angus Dreaver says. Especially this type, he says, where they think media are traitors, and they want them to know. “Four months ago, I was doing kids' TV.”

Dreaver thinks the generalisation works both ways. While the protestors see the mainstream media as a monolith and sweep them with one giant brush, “it’s important for us, conversely, not to see them that way.”

Von Keisenberg believes there are more moderates in the crowd than extremists. “I always felt there were enough people around me,” he says. And that made him feel safe in the first week when he was filming undercover, knowing that “if things did get violent, there would be some moderate ones who would stop them”.

He saw that in action, too. In his forays of the first week, when he joined the crowd unmasked to avoid attention. He saw a man there in his 70s wearing a mask. “The first thing he said to me was that he was immunocompromised, which is why he was wearing the mask.”

“It’s fine, mate. It’s a freedom rally, do what you want,” von Keisenberg proferred. But another protester came up and “tried to pull his mask off and started berating him, saying he had no identity. The mob mentality started and people around the gate joined in and started giving him grief.”

Von Keisenberg intervened. “Oi! chill out man. It’s a freedom rally, he’s free to wear a mask!” A woman close by turned around and said “Yeah, come on guys! leave him alone.” And they did.

'Mainstream media'

When people tell von Keisenberg that they don’t watch mainstream media, his follow-up is, “Well then, how do you know we are lying?"

“They say 'we get our news from Facebook, which is different’. Yeah, different, because there aren't many rules around it,” von Keisenberg says.

“Mainstream media is held more to account than social media,” Allen says. “But they think the opposite.”

Some of Dreaver’s acquaintances have shared his photos on Instagram, in posts that read “Mainstream media are liars.” “Bro, that’s me!”, he says.

Trying to remain objective in the face of constant harassment is a real challenge. “I am almost hyper-aware of that, where I am trying to capture the mundane and relax as much as the heightened states,” he adds. “And I am trying to not let my anger affect the pictures I take or how I cover it.”

But for camera operators, the task ends once they take the picture. “We only aim for clear sound and sharp, steady pictures,” Graham says. “The rest of the stuff is for other people to decide what to do with.”

Anderson thinks there are differences in perspectives within newsrooms. People who have watched the protests from a distance or from their desks often take a kinder view of the protestors, he says. “But me and the other camera ops, we copped a lot of abuse over three weeks. We just have a more bitter taste in our mouths for this crowd.”

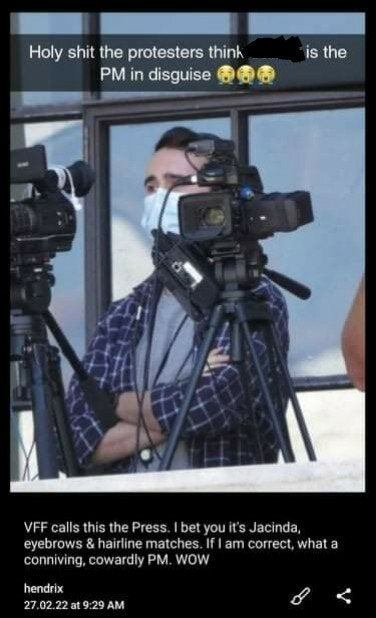

PM in disguise

There have been the fun moments, though, Anderson admits. There have been “raves” with young people dancing on the frontlines and he found himself almost filming to the beat. And there was a protestor who thought he was the prime minister in disguise.

A Reddit thread with a screenshot of a protestor’s post. Source: Reddit

“Now that is one theory I know is not true,” says his teammate, von Keisenberg. But how does he know for sure? “Because I have seen both of them in the same room at the same time.” And von Keisenberg has had his fun moments in the crowd, too. In one instance when he was filming undercover, a woman went on the stage and started talking into the mic about electric and magnetic fields ( radiation) and how crystals could block them.

“Bullshit!” von Keisenberg turned around and shouted.

“We are here for the mandates,” he added, not snapping out of character, and for the benefit of those around him who were listening to the woman speak.

A potential for violence

“The vibe changed every few days, and that was because people kept coming and going,” von Keisenberg says. “But there were always the elements who were there for whatever happened on day 23.”

One camera op I spoke to said there had been a “potential for violence” right throughout. And when someone like Winston Peters visits the crowd and says “the mainstream media have been gaslighting you for a long time,” it gives them validation, and lends credibility to their theories. But for those on the ground gathering news amid a hostile crowd, it exacerbates the possibility for harm.

Added to this potential of violence is the constant anticipation of things to come. “You have to be always prepared for when something will happen,” as Tiller puts it. “And that is exhausting.”

Emma Tiller on the Speaker’s balcony. "You feel like you have to be prepared for if something is going to happen, and that is exhausting."

“The day things turn to custard, you want to be there on the ground,” Graham) said to me a few days before the police operation. “You don’t want to be at home watching it on TV.”

And turn to custard it did; the threat of violence manifested itself on day 23. While the ‘battle’ raged between the police and the protestors, the media people found themselves being targeted.

Dreaver was in the crowd by the tent where a fire had started. “A Mainstream! We have got a Mainstream here,” a woman who spotted him started shouting. Brandishing a camping chair, she told him to “get out of here! Out! Out!” The riot police were advancing behind him and he stood his ground.

“She started hitting me on the back with it,” he said. “She didn’t have a lot of speed but it was still a metal chair.”

“It hurt a bit,” he reckons.

“Get out of here,” reckons the woman who attacked Dreaver with a chair. “Just go” shouts a man standing beside her. Screengrab from RNZ’s video story.

'Not everyone'

“There were some protesters who were trying to stop the violence. Even right at the end,” says Dreaver, recollecting how when some people were breaking up bits from the concrete slabs to get smaller throw-able chunks, another person tried to physically get in the way and stop them.

“But the other guys had a metal tent pole and whacked him over the head with it.”

Throughout the three weeks of protests, there had been repeated calls from the protestors asking the media to talk to them. On the morning of day 23 when I was filming from the Speaker’s balcony, a TV reporter had just finished a live cross into the bulletin. A man’s voice rang out from amongst the crowd, on the PA, inviting the media on the balcony to “come down and talk to real people and report the truth.” The same voice went on to berate us for wearing masks, behind which we were allegedly smiling smugly. Less than a minute after the initial invitation, he followed up with another call to step down so he could put a fist through the mask.

“Why don’t you come down to talk to us? Because getting bashed with a chair was always inevitable,” says Dreaver. “It’s crazy it took so long.”

Protestors whack another protestor with a tent pole as he tries to stop the violence. “ It didn't look as though it injured him, because the tent poles are quite light, but it looked quite gnarly,” Dreaver says. Screengrab from RNZ’s video story.

The aftermath

Parliament's grounds have been reclaimed. All but one street around the buildings is now open to the public. On Sunday, Te Āti Awa held a karakia to reinstall the mauri of the land. There is currently a rāhui over the parliament grounds. It is time for healing. And moving on.

“I was feeling sad last week. And then I look at Ukraine and realise there are bombs going off next to all these journalists and camera operators,” Dreaver. says “I got hit with a camping chair and I am going to sit around and complain about it?”

The effect of these protests linger though. Graham spent last Friday filming the hau kainga at Wainuiomata on high alert, and trying to keep the protesters from entering and setting up camp on their marae, as have other hapū around the capital. The crowd has dispersed but not vanished, and neither has their kaupapa.

“I have seen some of their kōrero online,” Graham says. The mandates might be gone soon, but “there will be other stuff,” he reckons.

“It’s definitely not over.”